Cardiff Castle as one sees it today is mostly of Victorian construction, but it was founded as a Roman fortified camp. A Norman castle keep on a mound (motte) was built within the walls. A medieval mansion followed. The keep was severely damaged in the English Civil war. The mansion went through various changes and extensions, most notably at the hands of the immensely rich 3rd Marquess of Bute and his architect and designer, William Burges.

Bute also had the perimeter walls you see today re-created on their Roman foundations.

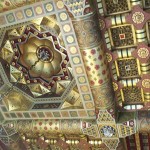

Some of Burges’ work can be seen on the exterior of the mansion, but the full effect is seen inside, where many room interiors can only be described as jaw-dropping, as Burges’ extravagant homage to the medieval period is given full reign.

Only about seven rooms are open to general visitors, and if you pay the £2.50 supplement for a guided tour, you are shown several more, but not the entire interior. In fairness, the typical room contains a vast amount of decorative detail for the eye to take in; a riot of colorful moldings, carvings, wall-painting and furniture.

Asides from the mansion, don’t miss climbing up the keep (if you are fit), and exploring Lord Bute’s tunnel built into his wall and extending around three sides of the site. The tunnel was used as a shelter during WWII and contains WWII relics, plus sound effects. In the cafe, look at a section of original Roman wall.

Despite the size of the site, it’s possible to have a look round it all in about two hours.

If you are travelling by car, you may prefer to use the city’s park and ride. When you get off the bus, ask someone to point you in the direction of the castle.

Category: House

Grand houses

Uppark, West Sussex

National Trust

Uppark is a Queen Anne style house and garden standing on a hilltop. It was built largely in its present form in the late 17th century. Some remodeling took place in the 18th and 19th century. It is a handsome house, and has some fine principal rooms with original contents. The gardens are attractive, and there are some interesting tunnels under the forecourt which connect the house with the stables and former kitchen outbuildings.

Uppark is known nowadays partly for the disastrous fire which occurred in 1989. The fire was started by heat from a workman’s blowlamp, and not discovered till it had taken hold in the roof. Firemen arrived promptly but were unable to halt the progress of the fire which destroyed the roof and upper floors and damaged the principal floor. The portable contents of the principal floor were rescued by firemen and volunteers before the upper floors fell into the principal rooms.

The decision was made to restore the house to its condition before the fire. The reconstruction was an epic of restoration. Today, the principal (ground) floor looks much as it did before the fire and is furnished with most of its original contents.

Grimsthorpe Castle, Lincolnshire

Private

Grimsthorpe Castle is a large country house in rural Lincolnshire, set in a 3000 acre park. Since 1516, Grimsthorpe has been owned by the holders of the Norman title, the Barony of Willoughby de Eresby.

Approaching the house along the drive, one sees the imposing North Front. Closer to, the East and West wings of a large square building are in a different style, while the South front, a Tudor-style jumble of gables, might be a totally different building.

The house was constructed in a number of phases. First there was a small castellated tower, which survives as King John’s Tower in the south-east corner. Then a Tudor house was attached to this, and later hastily extended to a Tudor house of four wings around a central courtyard. The Tudor North front was replaced by a newer one, which did not last long before it disappeared and was replaced by Vanburgh’s imposing North Front, which work extends as a skin about one-third of the way along the east and West sides. The last major change was to raise and re-skin the surviving Tudor East and West wings.

Inside, after entering the base of the left-hand front tower, one passes through a low vaulted hall before reaching one of a pair of staircases flanking the great hall, and getting a glimpse of the hall itself. Upstairs, one is directed into the State Dining Room, at first floor level in the tower, then southwards through the King James Room, State Drawing Room, and Tapestry Room in the east wing. After that, the South Corridor and West Corridor take the visitor around two more sides of an unseen central courtyard. One can look through doorways into various fine rooms.

Finally, one is allowed a limited view of the central courtyard, which contains an old tower at the west side, and a large single-storey service building to the north, adjoining the Great Hall.

Descending the north-east staircase, one is directed at ground level to the Chinese Drawing Room, with its fine wallpaper and oriel (bay) window, and the double-height Chapel in the tower. Vanbrugh’s Great Hall, with its superimposed arcades, is at the end of the visitor route.

There are many fine objects to look at during the tour, so if you think you did not spend enough time looking, you could go round again. If you go on a self-guiding day (Sunday) you will find helpful room guides in the main rooms and corridors.

There are two or three things that may affect your enjoyment of the visit. One is that the lighting in some of the rooms is very dim, reportedly to preserve fabrics and materials that are affected by light. This is common to many great houses, but the lighting in the King James room is so low that it is hard to see some objects clearly. One can not see out of any windows in most rooms.

The other is that no floor plan is included in the guidebook. In fact there seems to be no floor plan available anywhere. This is an irritant, since one cannot judge where one is within the building. Also, one cannot see what sections are excluded from the tour. In particular, one cannot judge from inside why the Tapestry Room is narrower than the State Drawing Room, something that a plan would make clear.

To remedy the plan deficiency, you can look at the Google Satellite view, which clearly shows the square courtyard and the irregular projections of the East wing and St John’s Tower.

Chartwell, Kent

National Trust

National Trust

Chartwell was the country home of British prime minister and war leader Sir Winston Churchill.

The site of Chartwell was built on from the 16th century, but the present house originated in the Victorian period. It was a brick Victorian house of no architectural merit, but Churchill bought it for its position and the views. It was transformed and extended by the architect Philip Tilden in a vernacular style of the kind made popular by Lutyens. In 1938 it had 5 reception rooms, 19 bed and dressing rooms, 8 bathrooms, and was set in 80 acres of grounds.

A tour of the house takes well under an hour, and it has to be said that the main interest is the Churchill connection. Rooms are displayed as they were in Churchill’s time, or contain exhibitions. Various rooms contain some of Churchill’s books. He owned many thousands of books, and made a living as a writer and historian. His histories of Marlborough, and of the English Speaking Peoples, of the Second World War etc. are still worth reading today. Volumes of his work can be seen shelved around the house. Many of Churchill’s own paintings are also on display. His art may not be to all tastes, but he was regarded as a serious artist. Below the principal ground floor is a lower floor that looks out onto the lakes. The kitchen on this level is preserved as it was in the 1930’s.

The grounds are very extensive, and contain formal gardens, lakes, woods, a swimming pool, a walled garden with a wall part built by Churchill, and some cottages with Churchill’s art studio.

Access is along narrow roads. The car park is of only moderate size, and when I visited on a March afternoon, it was full.

Ightham Mote, Kent

National Trust.

National Trust.

Ightham Mote (pronounced I-tam) is a medieval manor house that has survived for over 650 years in a valley in the Weald of Kent. It is entirely surrounded by a moat of running water, fed by a stream that traverses the gardens. The various owners were wealthy but not famed, and made modest changes to the house to adapt it to their needs and tastes. Much of the present outline of the house was in place by the 16th century. The house, with its cream stone and jumble of red-tiled roofs, sitting in a square moat, is very attractive.

If one stands in the central courtyard and looks around, it may look as if the house is of one piece and date, but in fact it is the product of six centuries. The earliest parts of the house date from the 1330s while other parts were built or altered at times from the Tudor to Jacobean to Victorian. The last owner bought the house in the 1950s and some rooms are presented with the decor of this period.

The house suffered sales of its entire contents on more than one occasion, and is presently furnished with furniture appropriate to the periods in which the rooms are presented.

Above the house to the north is a lawn and informal grounds, while to the west are a formal garden and some cottages on the site of the former stable block.

From 1990 to 2004 the house underwent a major programme of conservation during which much of the roof and timber-framed rooms were dismantled, and rotted and infested parts of the timbers cut out and replaced with new wood, before the whole was reassembled, so that the house now looks the same as before, but no longer crumbling. Hence most of the lath and plasterwork in the house is modern. On the other hand, without these repairs and also the repairs carried out in the Victorian period, parts of the house would have eventually fallen down. The conservation programme cost around £11 million.

Ightham Mote is well worth a visit, as it has some fine interiors and is one of the best moated medieval houses in the country.

Note that the approach to the house is along narrow roads.

78 Derngate, Northampton

The house at 78 Derngate, Northampton, was transformed by the Glasgow architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh from a modest Victorian terraced house to a building with unique modern designs. The client was W.J. Bassett-Lowke, founder of a prosperous local model-making and engineering business.

The house at 78 Derngate, Northampton, was transformed by the Glasgow architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh from a modest Victorian terraced house to a building with unique modern designs. The client was W.J. Bassett-Lowke, founder of a prosperous local model-making and engineering business.

The transformation was carried out in 1916-17. The Bassett-Lowkes moved on nine years later, and the house passed through various hands before the Northampton Borough Council obtained a 999-year lease in 1996. The house was Grade II* listed in 1965. Full restoration was undertaken in 2001.

The adjoining house, no 80, was included in the project and stripped out to provide modern access and exhibition space. (In old photos, no 80 appears to have a 2-storey high bay on the front).

No 82, also now interconnected, contains gallery space and a dining room/cafe.

The house was jointly designed by Mackintosh and his client. Inside, the basement kitchen was very modern for its day. Upstairs at street level the dining room looks modestly modern, while the hall/lounge looks nearly as bizarre as the photo below suggests. Most surfaces are finished in black, with a coloured frieze applied to the walls, and black furniture. The staircase is turned through 90 deg from its original (and more conventional) position, and is divided off by a lattice screen, also painted black at this level.

At first floor level are the principal bedroom and the bathroom. The bedroom is relatively conventional, and has a balcony. The bathroom was modern in its day and is papered with a washable mosaic design.

On the second floor are a study, repainted in the original colours, and the guest bedroom, which has a striking fabric backdrop to the twin beds which continues up the ceiling.

The house has been restored to its 1917 appearance. Some features are original. Some of the lost original features are replaced by near-equivalents which differ slightly from the originals, and the installation of furniture (usually replicas) seems to be a work in progress.

If you are interested in Mackintosh’s work, or modern design, this house is definitely worth a visit.

Nearby: The Museum & Art gallery, the Guildhall, and St Peter’s Church.

Getting there: there are multi-storey car parks for the Derngate theatres etc. Northampton railway station is a 20 min walk away.

Spencer House, London

Private

Private

Spencer House is one of the few surviving eighteenth-century grand London town houses, and almost the only one to retain its eighteenth-century interiors. Eight state rooms have been restored in the last ten years for RIT Capital Partners plc. Fireplaces, architraves, doors etc have been replaced to restore the full splendour of the house’s late eighteenth-century appearance.

This private palace was built in 1756-66 for the first Earl Spencer, an ancestor of the late Diana, Princess of Wales. Money was clearly no object. The exterior, by architect John Vardy, is in a Palladian style, and the interiors were designed by John Vardy and James ‘Athenian’ Stuart.

The ground floor has the entrance hall, Morning Room, Ante-room (with apsidal alcove) the Library, the Dining Room (with scagliola pillars) and the astonishing Palm Room.

Ascending via the Staircase Hall one finds the Music Room, Lady Spencer’s Room, the Great Room (aptly named, with curved, coffered and highly decorated ceiling) and the Roman-styled Painted Room.

The State Rooms have the original ceilings, generally highly ornate, and restored and very ornate fireplaces and woodwork. There is lots of gold-leaf gilding. The Palm Room has an unique palm tree design with gilded trunks.

The interior is really worth seeing. Furniture represents what was originally here, and a few pieces are the originals, returned to their original positions. There are also interesting paintings (some loaned from the Royal Collection) in most of the rooms.

The house is opened on Sundays, by guided tour. The unseen north and east wings of the house (presumably containing former service rooms and bedrooms) have been converted into lettable premium office space. Outside, facing St James’ Park, is a private garden, not opened to the public.

Access to the house is via St James’s Place, off St James’s Street, or via an alleyway from Queen’s Walk. (You may get an external view of the south side of the house from Little St James’s St, but I did not go there)

Interior photography is not permitted except for two rooms, but there is a pictorial tour on the Spencerhouse website, and floor plans can be found online.

18 Stafford Terrace, Kensington, London

(Visited as part of “Open House London.”)

18 Stafford Terrace was the home of Victorian cartoonist Edward Linley Sambourne, with his wife, children and live-in servants. The house is essentially unaltered since then, and presents an almost unique Victorian interior, dimly lit and with the expensive hand-made wallpaper almost covered by framed drawings, prints and paintings, and a dense clutter of furniture and collectible objects. There is stained glass in some of the windows.

On the free Open House day, I got to see (after queueing) the ground floor, part of the stairwell, and the Victorian loo. If you visit at another time, the 1.5 hour paid conducted tours go to all five floors. The contents of the basement are long gone and replaced by meeting room, shop, and modern toilets.

The house is now owned and operated by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

This should be an essential visit if you are interested in Victoriana.

Romanian Cultural Institute, London

Private

(Visited as part of “Open House London.”)

A mansion, speculatively built in the 1840’s and designed by George Basevi in a sort of classical-lite style. It’s in Belgrave Square, and I visited it because it was across the road from the Argentinian Embassy.

Contains a very English-looking fine panelled room downstairs and a suite of fine rooms with a French look, upstairs. I watched an interesting film about the Carpathian countryside, and saw a display about pioneer Rumanian aviator Aurel Vlaicu.

There are several other embassies nearby.

Click on images to enlarge)

Argentine Ambassador’s Residence, London

Private

Private

Visited as part of “Open House London.”

An elegant mansion at the north corner of Belgrave Square, speculatively built by Thomas Cubitt in the late 1840’s. It had been the scene of a number of political and cultural events, from the recruitment of nurses by Sidney Herbert for the Crimea, to being a haven for Argentinian volunteers during WWII.

During the Open House London weekend, the Residence had an exhibition of Argentinian textile art, as well as the permanent collection of interesting Eeropean and Argentinian art. The principal rooms are very opulent.