Private

Private

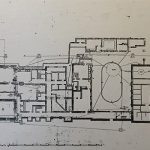

The current Copped Hall was built in the 18th century and extended in the Victorian period. The Georgian centre section was gutted by fire in 1917 and the mansion was further stripped of saleable materials in the early 1950s. The house remained a wreck within neglected grounds until acquired by the Copped Hall Trust in 1995.

To date, the mansion has been cleared of debris and vegetation, re-roofed, re-floored, staircases installed, and window shuttering or new windows fitted. The gardens have been cleared of overgrowth. Selected rooms have been re-plastered and decorated in Georgian style.

The house can be visited on certain days, principally by a guided tour of house and gardens that takes about two and a half to three hours. When I visited, this took in the grounds, including the site of the Elizabethan mansion with sunken gardens, the huge walled garden (Copped Hall Gardens on satellite view) containing among other things the ruins of a large number of greenhouses, and the squash court which is now a shop and tea-room. A sunken rockery garden with trees occupies part of the former cellar of the Elizabethan mansion.

The house tour included a maze of cellars extending below the whole mansion, the ground floor including the stables and an exhibition of agricultural or gardening equipment. Also included is a tour of the grand first floor, where one or two rooms have been replastered and decorated in Georgian style. One room had an exhibition of botanical drawings associated with the house.

The second and third floors can be accessed by a separate Hard Hat tour.

Various rooms contain furniture and other items typical of the house’s period, donated to the Trust. It appeared that some of the contents were intended to be viewed on a self-guided visit.

There is plenty to see at Copped Hall, and it is well worth a visit. Access is straightforward, but note that the mansion is north of the M25 which cuts across the former estate, while the entrance gate to Lodge Lane is to the south of the M25.

Category: Ruin

ruins of all kinds

Melrose Abbey, Roxburghshire

Historic Scotland

Historic Scotland

Melrose Abbey was founded in 1136 by Cistercian monks, but was largely destroyed by Richard II’s invading army in 1385. What remains today is largely a result of the subsequent rebuilding. It was still unfinished in 1504, and badly damaged by Henry VIII’s invasion of 1544. It appears that the nave was never finished. The Protestant Reformation took place in 1560. Subsequently the monk’s choir part of the church was adapted for use as a parish church, with added walls. A drawing of 1800 shows a roofless nave. In 1810 a new parish church was built in the town, and the abbey fell out of use.

Today the choir, transept and presbytery remain to full height while the monastery buildings remain only as foundation walls.

In 1822, Sir Walter Scott supervised extensive work to stabilise the ruins.

The interior was inaccessible when I visited due to concerns about unstable masonry. The outside of the choir, transept and presbytery on the south side are of particular interest because of the numbers of medieval carvings of gargoyles and other figures, including a bagpipe-playing pig.

Across a lane is a small museum in the ‘Commendator’s House’ containing carvings and other fragments found on the site.

Nearby are two small gardens curated by the National Trust for Scotland.

Roche Abbey, South Yorkshire

English Heritage

English Heritage

Roche Abbey was founded in 1147 and housed Cistertian monks till it was dissolved on the orders of Henry VIII. The buildings were despoiled in 1538, but the walls of the north and south transepts remain impressive, and low walls remain elsewhere.

The remains of a gatehouse stand beside open ground in front of the main site.

A fee is payable to walk on the site but the standing walls can be seen from a path running alongside. Access to the site is by a steep, narrow and bumpy lane, navigable by car.

Leiston Abbey

These ruins of an abbey built by Premonstratensian canons date mainly from the 14th century. Substantial ruins remain standing, some to full height. A side aisle is roofed and in use as a hall, and other parts are incorporated into a farmhouse, now in use as a school. An adjoining monastic barn is being restored and converted into a hall.

These ruins of an abbey built by Premonstratensian canons date mainly from the 14th century. Substantial ruins remain standing, some to full height. A side aisle is roofed and in use as a hall, and other parts are incorporated into a farmhouse, now in use as a school. An adjoining monastic barn is being restored and converted into a hall.

The remains of carved stonework and flint panelling can be admired at various points on the ruins.

Visit time ~30 mins.

Titchfield Abbey, Hampshire

English Heritage

The ruins of a 13th century Premonstratensian abbey were converted into a Tudor mansion, known as Place House, with a grand turreted gatehouse constructed across the nave. The house was dismantled after 1781.

The remaining structure, with towers, is quite impressive and well worth a visit. Still in position are fragments of tiled floors.

A free downloadable audio tour is available from the EH website.

Directions: Sat-nav delivers you outside the property, but the entrance, opposite a pub and to the right of a garden centre, is quite difficult to spot. If you drive through the narrow gated entrance, you should be able to park onsite. Admission is free.

Southwick Priory, Hampshire

English heritage

This was once a famous priory and place of pilgrimage. Now only part of the refectory wall survives.

Casual visitors may feel that tracking down and viewing this ruin is more trouble than it was worth. Some carved features remain.

Directions: The postcode takes you to a layby on the main road, alongside a long wall. The entrance is from Southwick village (right at roundabout, following the long wall). Park in the village car park. The entrance to the ruin is an inconspicuous metal footpath gate directly opposite the car park entrance, to the left of the sawmill. The EH sign is a few feet inside the gate. Follow the path through the wood. When you emerge at the golf course, the ruin is to your right.

Callanish Standing Stones, Lewis

Historic Scotland

Historic Scotland

The Callanish standing stones (Calanais in Gaelic) are a cross-shaped array of slim stones, centred on a circle of taller stones. The remains of a chambered tomb are in the centre. They were erected 4500 to 5000 years ago, making them one of the oldest man-made structures in Britain (or anywhere).

About 1000 years after it was constructed, the site was abandoned, and with a change of climate, the site gradually became blanketed with peat to a depth of about five feet, partly burying and preserving the stones. In the 19th century, with greater interest in monuments, the peat was removed and the site taken into State care.

The tall slim stones, with their mysterious alignments are an unique and striking sight. Well worth a visit.

Dun Carloway Broch, Lewis

Scottish Heritage

This broch, one of the best preserved in Scotland, is near the north coast of Lewis. It was probably built in the first century AD and remained in occupation for some time, till the floor level became too high because of occupation layers. It was last used as a stronghold in 1601, so presumably was largely intact at that time. Afterwards, the broch was partly destroyed and used for building stone.

Originally it is thought to have had tapering hollow walls, with a conical roof of timber and thatch on top, and at least one upper wooden floor. Staircases within the double walls gave access to the upper levels. The lower parts of the staircases still exist.

Inside, at ground floor level are several openings. These give access to a small guard room, the staircase, and an oval room where traces of peat ovens were found.

It is possible to climb onto the structure. Surprisingly, there are no signs telling visitors not to climb on the broch.

Because of its rarity, this is a most interesting visit. There is a visitor centre nearby.

Click on images to enlarge.

Bishop’s Waltham Palace, Hampshire

English Heritage

Bishop’s Waltham was a medieval palace used by the wealthy Bishops of Winchester. Also on the site is the Bishop’s Waltham town museum, in a farmhouse adapted from the palace’s lodging range.

There are extensive ruins of this large palace still standing.

I happened to be nearby in the early morning, so had a look over the wall, but was not able to get inside.

Worth a look if you are in the area. Admission free.

Hadrian’s Wall, Northumberland

English Heritage & National Trust

English Heritage & National Trust

Fragments of the wall remain at various places along its 71-mile length. However the most substantial remains are in the uplands where it was most difficult to rob the wall for purposes such as road-building, farm buildings and field walls. To the disgust of antiquaries, a lot of the wall disappeared when a military road was built alongside it in the 18th century.

At Housesteads, sections of wall remain to a height of several feet, and the complete outline and foundations of a Roman wall fort can be seen. The land is now owned by the National Trust. There is a National Trust building beside the car park, and a English Heritage museum and ticket office near the fort and wall, about half a mile up the hill.

It’s well worth making the effort to visit the site (unless it’s pouring with rain, as it was during my visit). While travelling there, look out for the vast Roman ditch systems alongside the road that runs parallel to the Wall. Two more forts, walks, and a view-point are within a few miles, making the area a candidate for an all-day visit.