I first visited Dunster Castle some years ago but this account is from April 2019. Dunster Castle is a former motte and bailey castle, now a country house, in the village of Dunster, Somerset, England. The castle lies on the top of a steep hill called the Tor, and has been fortified since the late Anglo-Saxon period. After the Norman conquest of England in the 11th century, William de Mohun constructed a timber castle on the site as part of the pacification of Somerset. A stone shell keep was built on the motte by the start of the 12th century, and the castle survived a siege during the early years of the Anarchy. At the end of the 14th century the de Mohuns sold the castle to the Luttrell family, who continued to occupy the property until the late 20th century.

The castle was expanded several times by the Luttrell family during the 17th and 18th centuries; they built a large manor house within the Lower Ward of the castle in 1617, and this was extensively modernised, first during the 1680s and then during the 1760s. The medieval castle walls were mostly destroyed following the siege of Dunster Castle at the end of the English Civil War, when Parliament ordered the defences to be slighted to prevent their further use. In the 1860s and 1870s, the architect Anthony Salvin was employed to remodel the castle to fit Victorian tastes; this work extensively changed the appearance of Dunster to make it appear more Gothic and Picturesque.

Following the death of Alexander Luttrell in 1944, the family was unable to afford the death duties on his estate. The castle and surrounding lands were sold off to a property firm, the family continuing to live in the castle as tenants. The Luttrells bought back the castle in 1954, but in 1976 Colonel Walter Luttrell gave Dunster Castle and most of its contents to the National Trust, which operates it as a tourist attraction. It is a Grade I listed building and scheduled monument. (source: Wikipedia).

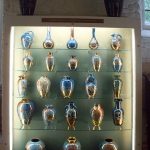

The interior of the house is interesting and various rooms on the ground and first floors can be seen. The gatehouse and other castle parts remain, but if you are expecting a medieval castle, look elsewhere!

The site has a number of pleasant walks curving around the hill. The top of the hill (above the house) is flat and laid as an open lawn. Below the hill is an old watermill to the south and the village of Dunster to the west. A folly tower tops a nearby hill to the north-east.

There are foot entrances from the village, but if arriving by car, the car park entrance is on the A39 north of the village.